How I Survived 3 Years in the Wilderness

[Originally published in YOU magazine July 2017]

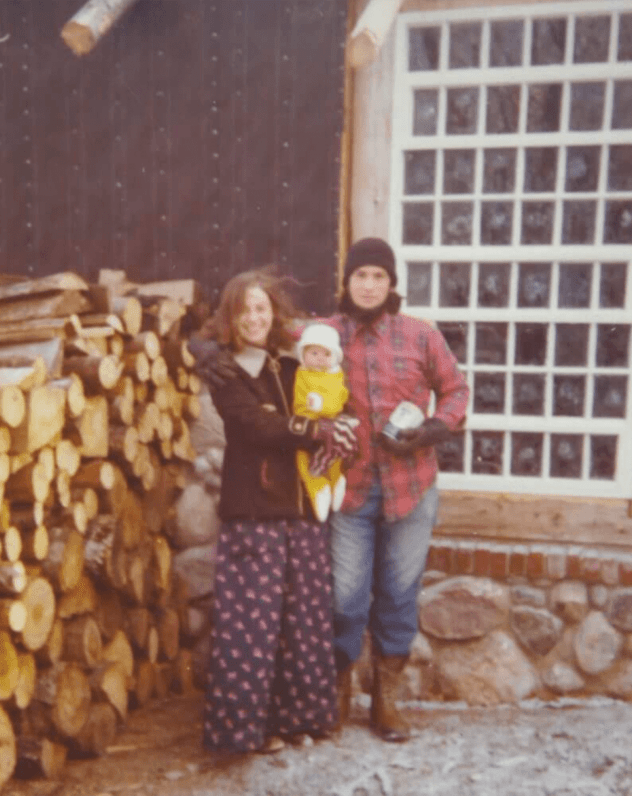

I’m sitting in a rocking chair wedged inside a cramped canvas tent, nursing my six-week-old daughter. Outside, tall bracken ferns and waist-high grasses blow in the wind, here in a clearing in a forest of maple and beech in Michigan’s vast and underpopulated Upper Peninsula wilderness. A chickadee calls, two clear notes; a crow answers from his favorite pine tree; an axe thwacks as my husband splits wood to build a fire for our morning coffee.

I’m sitting in a rocking chair wedged inside a cramped canvas tent, nursing my six-week-old daughter. Outside, tall bracken ferns and waist-high grasses blow in the wind, here in a clearing in a forest of maple and beech in Michigan’s vast and underpopulated Upper Peninsula wilderness. A chickadee calls, two clear notes; a crow answers from his favorite pine tree; an axe thwacks as my husband splits wood to build a fire for our morning coffee.

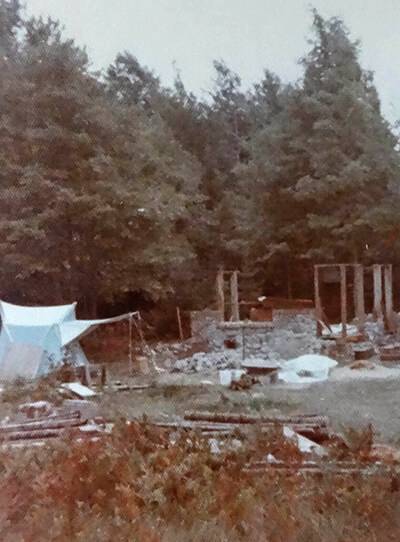

When my daughter is finished, I will join him in the day’s chores: heating water in a kettle on top of the campfire to wash our dishes, digging trenches for the foundation of the wood and stone cabin we’re building, hauling water from a nearby spring, cooking dinner and heating wash water on the campfire for ourselves and the dishes once again.

Much later, after the sun goes down and mosquitos chase us inside the tent, my husband will read aloud by the light of a kerosene lantern while I nurse our baby to sleep.

But right now, here in an antique rocking chair, inside a secondhand blue canvas tent, there is only my daughter and me.

* * *

“Wouldn’t it be cool if we could buy a piece of property somewhere and live off the land?” I asked my husband one day not long after we were married. “Get rid of the television and the telephone and build a cabin in the woods and grow our own food?”

Or possibly, my husband was the one who suggested the idea to me. It’s hard to say which of us came up with the proposal first, because this conversation took place forty-five years ago.

At the time, my husband and I were living in an upstairs flat in the middle of Detroit. I was eighteen, he was twenty-two. We’d met nine months earlier at an art show where we were both exhibiting, he selling miniature Calder-style mobiles, I the macramé belts and jewelry I had made.

We didn’t know a thing about living off the land—as we would find out soon enough when we discovered that the chainsaw we bought at a pawnshop was twice as heavy as it needed to be, and the antique cast iron wood-burning cookstove we snapped up at a used furniture store was completely inadequate as our cabin’s only source of heat because of its shoebox-sized firebox.

But the idea of building our home with our own hands, keeping sheep for wool, and growing our own food really appealed to us—much more than working at a job we might not even like, getting paid, and then going to a store to purchase the things we needed.

* * *

We weren’t alone in our thinking. During the 1970s, across the U.S., somewhere between 750,000 and one million people lived in communes as part of the back to the land movement, while millions more went off to farm the land on their own.

My husband and I considered communal living, and even spent a day and a night at a commune in Tennessee to see if that lifestyle would be a good fit. But in the end, we decided to go our own way. We pinched our pennies—buying powdered milk instead of fresh, giving up going to movie theaters, buying generic paper products and inexpensive cuts of meat—and in two years had saved enough to purchase ten acres of hardwoods in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. In June 1974, six weeks after our daughter was born, we drove three hundred miles north to pitch our tent ten miles from the nearest homestead, thirty from the nearest town.

Looking back, I’m astonished that we set off so cavalierly for an untried wilderness life—and with a new baby at that. But such is the fearlessness of youth. My mother couldn’t hide her tears as she said goodbye to her only grandchild, but we couldn’t wait to begin our grand adventure.

Our canvas home was cozy, but crowded. Our mattress and box spring took up most of the floor space, but we managed to squeeze in our daughter’s crib and a dresser with just enough room for the rocking chair. Our kitchen, we set up outside: the wooden table and chairs we’d painted a cheerful red and the kitchen cabinets we’d salvaged from a house earmarked for demolition beside the fire pit.

Euell Gibbons’s Stalking the Wild Asparagus served as our cookbook, teaching us which wild plants were safe to eat and how to fix them. Milkweed pods and wild mustard greens needed to be cooked in several changes of water to leach out the bitterness. Young cattail heads, boiled in salted water and nibbled like corn on the cob, tasted as good as anything we’d eaten from a supermarket.

Raccoons were a frequent nuisance, raiding our cupboards and threatening to knock over the cooling jars of wild apple-cherry jelly I’d slaved over for hours. Bears also occasionally came to visit—an empty beer can with bear-tooth-sized holes punched through it as proof. Once, while hiking with my daughter for an old orchard, we came upon a pile of dung that was so fresh, even this city girl knew the bear who’d left it was just around the next bend. I decided to abandon my apple-picking plans that day, since I couldn’t quite picture myself running from a bear and climbing a tree while carrying my daughter on my back!

Taking care of an infant without electricity and running water was sometimes a challenge. Washing diapers by hand in a bucket was every bit as disgusting as it sounds. Protecting her from insects was more easily accomplished, thanks to the mosquito netting covering I made for her crib. Cold was another matter. By the time we moved from the tent into our cabin, the overnight lows were barely above freezing. My daughter slept comfortably in layered fleece sleepers, but in the morning, when I stripped her down to change her wet diaper, the air was so cold, her little bottom was actually steaming. Still, the outdoor life clearly agreed with her, as she was never sick, and didn’t catch her first cold until she was four.

* * *

The months building our cabin were the happiest and most satisfying of our lives. We didn’t even keep a clock. We got up when it got light, and went to bed when it got dark, while the hours between were filled with activity of our own choosing: building our home, foraging for food, going for a swim or a hike whenever we had the urge.

Many people dream of trading the bustle of city life and the pressures of social media for a self-sufficient lifestyle in tune with nature. But we discovered that self-sufficiency is more difficult to attain than some might think, requiring a level of knowledge, experience, and resources that we simply didn’t have. There were many items we needed, such as gasoline for our car and for our chainsaw, that we couldn’t provide ourselves—which is why, after our cabin was finished and our savings had run out, my husband took a job with a local builder. And if you cut yourself and need stitches, as happened to us more than once (that pesky chainsaw!), you really need a doctor to sew you up, and thank goodness for the small-town hospital thirty miles away.

Our grand homesteading adventure came to an end after just three short years—not because we had failed, but because our priorities had changed. The school our daughter would soon attend necessitated an hour-long bus ride, and it was difficult to imagine subjecting a five-year-old who had grown up in the woods to that. At the same time, my husband had landed a plum job as a meat cutter in a grocery store, but this meant he also now had a commute. And we still didn’t have a telephone or running water.

* * *

So, we sold our cabin, and moved to the small town where my husband’s job was based. As our family grew, we both took on a variety of work, mainly of our own devising: sewing and alterations, offering violin lessons, office and carpet cleaning, furniture reupholstering. The Upper Peninsula is a challenging place to make a living, but it’s a wonderful place to raise a family. The things some might consider hardships, such as having to drive fifty-five miles to go to a movie, we saw as advantages. Our children learned to be independent, not to look to material things for their happiness, to be self-contained, and to engage in creative activities of their own devising without the distractions of living in a city. Most importantly, they learned not to be afraid to try something that others might consider too daring.

“When I decided at age twenty-one to move to South America,” our oldest daughter recalls, “I was baffled when people asked if my parents were worried about me, because I knew they had made a similar leap at my age.”

“Nature was such an important part of my life growing up,” our middle daughter adds. “Trips to the Lake Michigan sand dunes, hikes in the woods, watching the Perseid meteor shower on a cold beach at night are some of my fondest memories—and I still do those things today.”

The most enduring lesson we learned from the three years we lived in our cabin is that we are all connected. We need each other. In preparation for our move, we read how-to books such as the Whole Earth Catalog and the Foxfire series, which taught us how to split cedar shingles and how to make soap. But it was the people we met—our neighbors—who were the real help.

People gave us produce from their gardens. An old couple let us tear down a hundred-year-old farmhouse in exchange for the lumber. Farmers gave us permission to collect rocks from their fields for our cabin’s foundation. One logger showed my husband how to sharpen his chain saw. Another used the claw of his logging truck to lift the massive ceiling beams my husband had cut and hewn onto the framework of our cabin.

Some say the folks who live in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula are more helpful than most because isolation forces them to rely on each other. This might be true. All I know is that the generosity of our U.P. neighbors taught us it’s people who make a place truly special.

Thirty years after we pitched our tent, my husband and I moved back to Detroit; mainly for employment reasons, but also to be closer to our aging parents. But the years we lived in the Upper Peninsula instilled in us a love of wild places and an ease with nature that shape us to this day. We will never forget our homesteading days, and the wild and beautiful place that still owns a big piece of our hearts.

© Karen Dionne